A Journal of Foreign Policy Issues

The Soviet threat and the American response to it created a bipolar world:

two superpowers locked in a head-on confrontation, with many of the other countries

joining the coalitions created by the two superpowers. In such an environment, the

foreign policy doctrine elaborated on by the American leadership was the well-known

“containment doctrine,” namely, the attempt to contain the Soviet Union and restrict

its expansion in the hope that the inherent weaknesses of the Soviet system would lead,

sooner or later, to its collapse.

In this context, the US created a network of multilateral

and bilateral alliances (NATO, SEATO, CENTO, ANZUS) that successfully lined up against

the Soviet coalition. The US also created an international economic system through a series

of agreements and aid programs for its allies, as well as economic organizations, such as

the Bretton Woods Conference, the Marshall Plan and the OECD. These contributed to the

strengthening of the western coalition, and led finally, to the collapse of the Soviet Union.(1)

In this context, the US created a network of multilateral

and bilateral alliances (NATO, SEATO, CENTO, ANZUS) that successfully lined up against

the Soviet coalition. The US also created an international economic system through a series

of agreements and aid programs for its allies, as well as economic organizations, such as

the Bretton Woods Conference, the Marshall Plan and the OECD. These contributed to the

strengthening of the western coalition, and led finally, to the collapse of the Soviet Union.(1)

Today things have changed. We are facing a more complex international system, which, unlike the straightforward rigid bipolarity of the previous one, is fluid and unpredictable. The threats to this new international system are no longer clear and one-dimensional, but multipolar and diffuse. They are expressed at different levels and display different degrees of intensity. There is no longer a large and obvious threat, such as that of the Soviet Union against the western community. On the contrary, there are now multiple, low-intensity threats, and the consensus for dealing with them is much more difficult to achieve among the western allies. The security and defense issues that concern the western community have thus risen sharply in number.

Military power is now only one of the components of national power, while competition among the great powers has moved from the military to the economic field. Today, economic issues as well as those concerning energy, trade, and technology claim priority in the elaboration of the post-Cold War strategy of the West.(2)

Another factor that further complicates post-Cold War security concerns the new form under which the international system now operates. This is now in a state of development, as shown by the dramatic changes in actors, actions, and the distribution of power. The outcomes of such changes are uncertain. Will they lead to policies of balance of forces after a redistribution of power among the great powers (Germany, China, Japan, the US, Russia)? Will the present situation evolve into a new competition between West and East, or will there, on the contrary, be a continuous and peaceful understanding among the great powers?

The remarkably stable and predictable

cold war climate is gone, and the question is whether the world is reverting to a multipolar

system, stable but all too war prone. In many ways, however, as Waltz has argued, bipolarity

endures but in an altered form.(3) “Bipolarity continues because militarily Russia can still

take care of itself and because no other great powers have yet emerged. Russia’s ability to play

a military role beyond its borders has diminished, yet nuclear weapons ensure that no state can

challenge it.”(4) Nuclear weapons alone, however, do not turn states into great powers. Russia

will not remain a great power unless it is able to use its resources effectively in the long run.

Its nuclear capability only enables it to shift resources from the military sector of its economy

to civilian ones. While it is trying to do so,

its large population, vast resources, and geographic

presence in Europe and Asia compensate for its many weaknesses. “Short of disintegration, Russia

will remain a great power-indeed a great defensive power-as the Russian and Soviet states were

through most of their history.”(5)

its large population, vast resources, and geographic

presence in Europe and Asia compensate for its many weaknesses. “Short of disintegration, Russia

will remain a great power-indeed a great defensive power-as the Russian and Soviet states were

through most of their history.”(5)

Some of the implications of bipolarity, however, have changed. Throughout the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union held each other in check. With the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the United States is no longer held in check by any other country or combination of countries.(6)

Huntington argues that what we are in fact experiencing at the systemic level is a peculiar hybrid, which he calls the uni-multipolar system. He admits that there is only one superpower in the international system but he argues that this does not necessarily make the world uni-polar. “A uni-polar system would have one superpower, no significant major powers, and many minor powers. As a result, the superpower could effectively resolve important international issues alone, and no combination of other states would have the power to prevent it from doing so.” (7) The international system is not multipolar either, according to Huntington, because a multipolar system is characterized by “several major powers of comparable strength that cooperate and compete with each other in shifting patterns.”

In fact, the international system is in a transitional

phase from a uni-polar to a multipolar model, where we can discern elements of both. The rudimentary

rules of this system are the existence of a single superpower, the United States, with preeminence

in every domain and the ability to project its power and promote its interests in every part of the

globe. At the same time, as Huntington argues and as we experienced in Kosovo, the settlement of

international issues requires leading action by the superpower, but with some combination of other

major powers.

On the other hand, no combination of major powers can take action on major international

issues without the consent of the superpower. (8)

On the other hand, no combination of major powers can take action on major international

issues without the consent of the superpower. (8)

At a second level, this uni-multipolar system contains major regional powers that cannot project their power and interests globally. In the current global circumstances, such powers include Russia in Eurasia, France and Germany in Europe, China in East Asia, India in South Asia, Iran in Southwest Asia, Brazil in Latin America and South Africa, and Nigeria in Africa.(9) At a third level, there are secondary regional powers whose interests conflict with the more powerful regional states, and who play the role of geopolitical pivots.(10) “Britain in relation to the German-French combination, Ukraine in relation to Russia, Japan in relation to China, Pakistan in relation to India, Argentina in relation to Brazil, Saudi Arabia in relation to Iran.”(11)

There is also the case of Western Europe. The achievement of unity would produce an instant great power, but Europe is far from a final decision to form a single, effective political entity with common foreign and defense policies. Despite difficulties, two factors may enable Western Europe to achieve political unity. “The first is Germany, the second is the US Uneasiness over the political and economic clout of Germany, intensified by the possibility of its becoming a nuclear power, may produce the final push to unification. Europeans also doubt their ability to compete on even terms with the US unless they are able to act as a political as well as an economic unit. If the EU fails to become a single entity, the emerging world will nevertheless be one of four or five great powers, whether the European one is called Germany or the US of Europe.” (12)

In any case, France and Germany are the most important players in the western section of Eurasia. Both countries have their own vision of a unified Europe but differ in their view of their relationship with the United States. France in particular, “has its own geo-strategic concept of Europe, one that differs in some significant respects from that of the U.S., and is inclined to engage in tactical maneuvers designed to play off Russia against America and Great Britain against Germany, even while relying on the Franco-German alliance to offset its own relative weakness.”(13)

Moreover, both France and Germany have the power and the will to exercise a wider regional influence. France not only seeks a central role in unifying Europe but also sees itself as the nucleus of a Mediterranean-North African cluster of states that share common concerns. Germany has recently shown an inclination to play a more prominent role in the world. Germany is increasingly conscious of its status as Europe’s leading state in both economic and conventional military power, although for some years to come the eastern part of Germany will be a drain on its economy.(14) Moreover, both France and Germany maintain a special relationship with Russia. Some analysts even fear that Germany even retains, “the grand option of a special bilateral accommodation with Russia.”(15)

Great Britain, according to Brzezinski, does not fit the definition of a geo-strategic player. “It has fewer major options, it entertains no ambitious vision of Europe’s future, and its relative decline has also reduced its capacity to play the traditional role of the European balancer. Its ambivalence regarding European unification and its attachment to a waning special relationship with America have made Great Britain increasingly irrelevant insofar as the major choices confronting Europe’s future are concerned. London has largely dealt itself out of the European game.”(16)

Russia remains a major geo-strategic player, despite its current weakness. Currently, Russia is unable to project power beyond its borders, but its very presence has a decisive impact on the choices of the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union. If Russia manages to avoid disintegration and recovers its strength it will exert a considerable amount of influence upon its western and eastern neighbors. More importantly, however, the future of events in Eurasia will depend upon Russia’s relationship with the United States and whether this will be cooperative or antagonistic. According to Brzezinski, “much depends on how its internal politics evolve, especially on whether Russia becomes a European democracy or a Eurasian empire again. In any case, it clearly remains a player, even though it has lost some of its ‘pieces’ as well as some key spaces on the Eurasian chessboard.”(17)

A few words are warranted on Ukraine’s importance, especially in relation to Russia. “Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire. Russia without Ukraine can still strive for imperial status, but it would then become a predominantly Asian imperial state. If Moscow regains control of Ukraine, with its 52 million people and major resources as well as its access to the Black Sea, Russia automatically again regains its wherewithal to become a powerful imperial state, spanning Europe and Asia.”(18)

The other medium-sized European states by virtue of being members of NATO or the EU, either follow America’s lead or that of France or Germany. Their policies do not have a wider impact and they are not in a position to alter their basic alignments.

Competing Visions of US Strategy in the Post-Cold War System: International Interventionism or Isolationism?

The dramatic changes in the international system, following the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, required the United States, the remaining superpower, to reconsider its national security policy and its position and role in the international system and world affairs.

The isolationist tendency has always been a clear trend in the formulation of American foreign policy. This trend is due to two reasons, one cultural and the other geopolitical. The first is the deeply established conviction of the existence of an American exceptionalism, namely that America was created on the basis of democratic and humanitarian principles and differs radically from the intrigues and balance of power considerations of the “Old World” of the European continent. The second reason is the advantageous geographic position of America, which offers security from foreign threats. Moreover, nuclear weapons guarantee the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the United States. Since the United States is “strategically immune,” the argument goes, interventionism in world affairs is not only unnecessary but also counterproductive.

The supporters of this trend were marginalized during the Cold War, as American foreign policy successfully combined interest with morality in the eyes of the American people and secured popular support for a series of presidents, from Truman to Bush, legitimizing international interventions. The new isolationists have adopted a restricted view of US national interests and prefer the term disengagement to isolationism. They enjoyed a meteoric rise in the public arena with Patrick J. Buchanan’s candidacy for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination, but they have not had an impact in the formulation of post-Cold War American strategy.(19)

Interest of Morality?

In order to gather support for an interventionist foreign policy in the post-Cold War era, the present American leadership has had to formulate a foreign policy that would combine the promotion of American national interests with the messianic perception of morality, democracy, and human rights-and do this in a convincing way, as they did during the Cold War.

The two ideologies that have traditionally influenced the formulation of American foreign policy are liberal idealism and political realism. American liberals think of the state as a factor of reform and aspire for it to have an expanded role, even in supporting military interventions, provided they are carried out to serve democratic ideals and promote American values. On the other hand, the more conservative realists are in favor of “less state”, and support international interventions when they concern security matters and the promotion of America’s national interests.

This distinction was more difficult during the Cold War, as the conservatives supported continuous interventions against the communist regimes, often with the assistance of states with reactionary and even oppressive regimes. This amoralism led many a liberal to a form of neo-isolationism.

At the end of the Cold War, things were restored up to a point. Liberals have leaned again towards international interventionism, while conservatives have become more selective. The war in Bosnia is an example of this development. In this case, the liberals opposed to America’s involvement in Vietnam were the ones demanding American military involvement in Bosnia and Kosovo. On the contrary, with the disappearance of the communist threat, the conservatives argued that no “vital interests” were at stake to justify American involvement. The same distinction was made when America invaded Haiti in order to restore democracy.

Concerning political realism, the most basic post-Cold War geopolitical aims of the US refer to: controlling Eurasia as well as the energy resources in the Middle East and Central Asia; containing China; and attempting to prevent the creation of local powers in regional subsystems, especially if they are hostile to American interests.

What the realists are searching for is a way to implement these aims. Realists, such as David Abshire, director of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, have argued in favor of a flexible and selective international interventionism, according to which the US would get involved only in cases when its strictly defined vital interests are at stake.(20) Proponents of this “selective engagement” argue that the United States should engage itself abroad, in places like Eurasia, in order to maintain a balance of power and avert a great power war. (21)

Other realists, however, argue that the US should choose and impose any strategy it wishes, since it is the only superpower left in the world. Some have even spoken openly in favor of the establishment of an “American empire.”(22) According to this school of thought, the US should not just be primus inter pares; it should be primus solus. Consequently, the US must “maintain the primacy with which it emerged from the Cold War.”(23) The objective for primacy is not merely to preserve peace among the great powers but to preserve US supremacy by politically, economically, and militarily outdistancing any global challenger.(24) Threats against such a form of American domination may come from a nationalistic Russia, which has led many analysts to argue in favor of NATO expansion.(25) Moreover, “in Europe, the United States would work against any erosion of NATO’s preeminent role in European security and the development of any security arrangements that would undermine the role of NATO, and therefore the role of the United States, in European security affairs. The countries of East and Central Europe would be integrated into the political, economic, and even security institutions of Western Europe. In East Asia, the United States would maintain a military presence sufficient to ensure regional stability and prevent the emergence of a power vacuum or a regional hegemony. The same approach applied to the Middle East and Southwest Asia, where the United States intended to remain the preeminent extra-regional power.”(26)

In the post-Cold-War era, neoliberals support the expansion of democracy and free market economy, as well as the establishment of a new international legal order. Tony Smith has argued that the promotion of democracy was, and still is, part of the U.S.’s national security policy.(27) The neoliberal idealists have in effect abandoning the Westphalian system in favor of a new interventionist regime based on the assumption that the core threat to international security in the post-Cold War era does not emanate from interstate conflict, but from conflict within states.(28)

In essence they advocate the abandonment of the old idea of sovereign equality, “the erstwhile notion that all countries, huge or small, are equal in the eyes of the law,” exemplified by the UN Charter rules that strictly limited international intervention in local conflicts.(29)

The Case of Kosovo

The Bush administration broadly subscribed to the principles of primacy, as evidenced by the commentary made by former Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney and the administration’s Defense Planning Guidance (DPG), which was leaked to the press in March 1992.(30)

The first Clinton administration was characterized by indirection and ad hocism in international affairs. It drew upon selective engagement, primacy, and liberal idealism. The first concise vision of the Clinton administration, proposing a shift from containment to enlargement, was put forward by the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, Anthony Lake, in 1994 and was adopted by the administration in a 1996 White House document.(31) The Clinton administration spent a good part of its second term absorbed by the domestic political crisis of impeachment. When the crisis was over, the Clinton administration slipped into a quest for primacy, best exemplified by US policy in Eurasia.

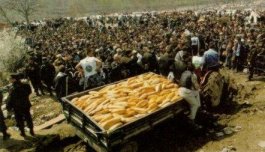

The Soviet Union’s disintegration resulted in a geopolitical vacuum in central-eastern Europe, the Balkans, and Central Asia. American governments have not resisted the temptation to fill this vacuum and consolidate the gains of Cold War victory. For the United States, Eurasia is clearly the trophy of its victory in the Cold War. More importantly, its global primacy, according to its leading geopolitician, Zbignew Brzezinski, will be directly dependent on how effectively its preponderance on the Eurasian continent is sustained. Brzezinski advocates a more forward policy around the Russian periphery. He claims that the area, which extends from the Adriatic to the border of the Chinese province of Sinkiang, and from the Persian Gulf to the Russian-Kazahk frontier, will be riven by ethnic conflict and weapons of mass destruction-”a whirlpool of violence.”(32)

In the former Yugoslavia, US interests combined both humanitarian values advocated by neoliberal idealism and geopolitical concerns voiced by the advocates of US primacy.(33) Once NATO got involved, as the only institution that could implement this new interventionist post-Cold War policy and the only institution capable of military heavy lifting, its credibility became an issue in itself. “A success in Kosovo would guarantee the primacy of NATO in Europe’s future. There would be no doubt that NATO was the preeminent and indispensable security institution on the continent.”(34)

Peter W. Rodman wrote in the last issue of Foreign Affairs that “an outcome short of victory-say an ambiguous compromise that leaves Milosevic in power in Belgrade and still holding on to a Kosovo depopulated of most ethnic Albanians-will bring these idealistic hopes down to earth.”(35) Indeed, the Kosovo legacy might prove to be a mixed bag.

Skeptics among neoliberal idealists fear that Kosovo might discredit the new interventionism. By hinting on future NATO action in other “humanitarian catastrophes,” new interventionists have wagered NATO’s future on its ability to solve ethnic conflicts divorced from a strategic national interest. But even advocates of this new interventionism agree that it is dangerous for NATO to rewrite the rules unilaterally by intervening in domestic conflicts on an irregular, case-by-case basis. Glennon summarizes it aptly: “Case-by-case decisions to use force, made by the users alone, are not likely to generate such support. Justice, it turns out, requires legitimacy; without widespread acceptance of intervention as part of a formal justice system, the new interventionism will appear to be built on neither law nor justice, but on power alone. Ultimately, the question will be empirical: unless a critical mass of nations accepts the solution that NATO and the US stand ready to offer, that solution will soon be resented.”(36)

Skeptics among realists argue that by acting as if this were a uni-polar world, the US is also becoming increasingly isolated. States that were willing to accept the US as a “benign hegemony” assumed that it would mean the emergence of multipolarity, where economic sanctions and military intervention would be legitimated through some international organization such as the UN. Huntington argues that “the community for which the US speaks includes, its Anglo-Saxon cousins (Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand) on most issues, Germany and some smaller European democracies on many issues, Israel on some Middle Eastern questions, and Japan on the implementation of UN resolutions. These are important states, but they fall short of being the global international community. Instead, the US is becoming increasingly isolated, with elites of countries comprising two-thirds of the world’s people-Chinese, Russians, Indians, Arabs, Muslims, and Africans-seeing the US as the single greatest external threat to their societies.”(37)

It seems that in these transitional periods, unilateral actions and intervention will only foster and accelerate the creation of an anti-hegemonic coalition. This has not yet happened, but Kosovo has led to some anti-hegemonic cooperation. Meetings of the leaders of Germany, France and Russia, the Sino-Russian rapprochement, and the “strategic triangle” between Russia, China and India promoted by former Russian Prime Minister Yevgeni Primakov are initial attempts at counterbalancing the United States. Huntington argues that the US should instead adopt the Bismarckian strategy and take advantage of its position in the international system and its resources to elicit cooperation from other major powers to deal with global issues. Such a return to multi-polarity and benign hegemony would have a stabilizing impact on the international system and prove, in the long run, beneficial to US interests.(38)

Endnotes

1 Ronald Steel, Temptations of a Superpower, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995).

2 Robert S. Borosage, “Inventing the Threat.” World Policy Journal 10, no.4 (Winter 1993-94), p. 9.

3 Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Emerging Structure of International Politics” International Security, vol. 18, no. 2 (Fall 1993), pp. 44-79.

4 Ibid, p. 52.

5 Ibid, p. 52.

6 Waltz argues that if we understand balance of power to be a recurring phenomenon rather than a particular and ephemeral condition we can predict that other countries, alone or in concert, will try to bring American power into balance. All the more so because a country wielding overwhelming power cannot be expected to behave with moderation for long. Ibid.

7 Samuel P. Huntington, “The Lonely Superpower” Foreign Affairs (March-April 1999), vol. 78, no. 2, p. 35.

8 Ibid, p. 36.

9 Ibid, p. 36.

10 Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard, (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1997), pp. 40-41.

11 Huntington, “The Lonely Superpower,” p. 36.

12 Kenneth Waltz, “The Emerging Structure of International Politics,” p. 70.

13 Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard, p.42.

14 Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard, p. 62.

15 Ibid, p. 42.

16 Ibid, p. 42.

17 Ibid. p 44.

18 Ibid. p 44.

19 The most articulate version of this new version of isolationism is Eric Nordlinger’s Isolationism Reconfigured: American Foreign Policy for a New Century (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995).

20 David M. Abshire, “US Global Policy: Towards am Agile Strategy”, The Washington Quarterly 19, pp. 41-61; Robert Art, “A Defensible Defense: America’s Grand Strategy After The Cold War,” International Security, vol. 15, no. 4 (Spring 1991): pp. 5-53; Stephen Van Evera, “Why Europe Matters, Why the Third World Doesn’t: American Grand Strategy After the Cold War,” Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 13, no. 2, (June 1990): pp. 1-51.

21 Barry R. Posen and Andrew L. Ross, “Competing Visions of US Grand Strategy,” International Security, vol. 21, no. 3 (Winter 1996-97): p. 17.

22 Jacob Heilbrunn and Michael Lind, “The Third American Empire”, New York Times, January 2, 1996.

23 Barry R. Posen and Andrew L. Ross, “Competing Visions of US Grand Strategy,” p. 32.

24 Ibid.

25 Henry Kissinger, “Expand NATO Now,” The Washington Post, December 19, 1994.

26 Barry R. Posen and Andrew L. Ross, “Competing Visions of US Grand Strategy,” p. 34.

27 Tony Smith, America’s Mission: The United States and the World Wide Struggle for Democracy in the 20th Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

28 Michael F. Glennon, “The New Interventionism. The Search for a Just International Law,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 78, no. 3, (May/ June 1999): pp. 2-7.

29 Ibid.

30 “The DPG is the high level strategic statement that launches, and in theory governs, the Pentagon’s annual internal defense budget preparation process.” The DPG stated that “Our first objective is to prevent the reemergence of a new rival, either on the territory of the former Soviet Union or elsewhere, that poses a threat on the order of that posed formerly by the Soviet Union. This is a dominant consideration and requires that we endeavor to prevent any hostile power from dominating a region whose resources would, under consolidated control, be sufficient to generate global power. Our strategy must now refocus on precluding the emergence of any potential future global competitor.” Barry R. Posen, and Andrew L. Ross, “Competing Visions of US Grand Strategy” p. 33; Dick Cheney, “Active Leadership? You Better Believe It,” New York Times, March 15, 1992; “Excerpts from Pentagon’s Plan: Prevent the Emergence of a New Rival” New York Times, March 8, 1992.

31 A National Security Strategy of Engagement and Enlargement (Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office, February, 1996; Barry R. Posen and Andrew L. Ross, “Competing Visions for US Grand Strategy”.

32 Zbignew Brzezinski, Out of Control: Global Turmoil on the Eve of the Twenty-First Century.

33 Joseph S. Nye, Jr. “Redefining the National Interest,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 78, no. 4, (July/August 1999): pp. 22-35.

34 Peter W. Rodman, “The Fallout from Kosovo,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 78, no. 4, (July/August 1999): pp. 45-51.

35 Ibid, p. 47.

36 Glennon, “The New Interventionism.” p. 7.

37 Samuel P. Huntington, “The Lonely Superpower.” p. 41-43.

38 Ibid, p. 48.